Early on in my career I asked a Fundraising Director what were the two things I most needed to be a good major donor fundraiser. She told me it was to know as much about the charity as the CEO and to be able to suck up to people. Hardly stellar advice.

Even as a rookie, I knew the combination of sycophancy and too much knowledge was actually counterproductive to the goal. If trust is the key component for giving, how is it possible to build it under such insincere terms? And was it really necessary to know everything? Wasn’t that what experts were for?

Like a lot of fundraisers, I didn’t start out wanting to be one. Up to that point my working life had taken a number of turns, some of which had gravitas, others were just plain hilarious (yes I did once earn a crust answering Shirley Bassey’s fan mail). But whether it was acting, producing events or managing artists, the one common thread running through was that it was always about bringing people together.

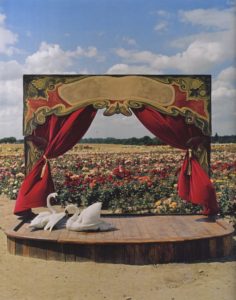

Many of the soft skills needed to be an effective major donor fundraiser you don’t necessarily gain in a development role. Everything I know about relationship building and the dynamics between people I learnt in the theatre. From the mechanics of acting through to the business end of West End production, it has a lot to teach fundraisers about relationships and how to build high performing teams fast. You want the best example of when a group of disparate people work together to tell a story to their optimum ability within a finite period of time? This is exactly what happens when you rehearse a play.

Here are some of the most interesting observations I’ve made about the parallels between theatre and relationship fundraising:

Status is all about perception: I once saw a production of Anthony and Cleopatra with Helen Mirren in the title role. Consummate actress as she is, it didn’t matter how much regal posturing La Mirren did, no one on stage was showing her any respect. The actors were sloppy and unfocused and consequently the audience were unable to believe what she was really capable of, namely having anyone around her beheaded/imprisoned/exiled at a moment’s notice.

One of the first lessons you learn at drama school is the nature of status and how it is essential to creating dramatic tension. Status on stage is exactly the same as it is in life. It may look like someone is radiating power and privilege but what they’re really doing is soaking up the rays of other peoples’ perception. Without this their status is an illusion and holds no weight. This is a really useful thing to remember when you are in a donor meeting with someone who is a high status player.

Playing your objectives – I was horrified when my acting teacher told me that people went through life not showing who they were, but attempting to get what they wanted. That in every dramatic scene there were a series of mini objectives leading to a super objective and it was up to the actor to work out what those objectives were and then play them. In my idealistic early twenties, this seemed calculating and manipulative.

When you consider it, fundraising is a benign manipulation. Our donor cultivation is a series of carefully considered and bespoke steps that we hope will lead to the solicitation of a gift. This isn’t – or at least shouldn’t be – a hit and miss situation, but something with its roots in a process because unless specific actions are taken, nothing will happen and our fundraising lives become thwarted by desk research and blue sky thinking. Understanding your distinct objectives for each donor and then playing them is the only way to move any relationship forward.

Emotional intelligence is king: I once worked for a man who was promoting a West End musical headlining a certain diminutive star. The actress had been out of work for some years and on the day of the press junket, he asked me to buy some flowers to present to her in front of the journalists.

This was a nice touch of appreciation, but he took it one step further, making a point of requesting a round posy rather than something long and trailing, so it didn’t make her look shorter and feel additionally self-conscious about her height. She was delighted by the thoughtful gesture and felt far more comfortable about the task ahead because she had been publicly validated in an appropriate way.

Right here is a perfect lesson in donor management. The promoter had a fundamental understanding of how she was feeling in that moment – perhaps insecure or exposed, certainly under pressure – and he made steps to acknowledge and address this before anyone else had thought of it. None of this is about the intellect. He was flexing an entirely different muscle.

Sometimes as fundraisers we plough ahead without checking in to test the emotional temperature. With one eye on our punishing targets, we may push someone along an avenue down which they’re not ready to travel or wrongly assume that their silence is something to do with us. Taking a holistic view of the situation from the donor’s perspective and then responding accordingly makes you stand out and builds trust and loyalty. Without getting all Oprah Winfrey here (OK, I will get a bit Oprah Winfrey) it’s about letting someone know that you’ve heard them and that what they’ve said – or more often than not what they’ve indicated – has meant something to you.

React, react, react: Good acting always stems from good listening. I’ve been in many networking situations with non-fundraisers (and if I’m honest, some actual fundraisers too) where I’ve watched the donor or prospect glaze over as they are battered with facts, information and opinions and yet still the onslaught continues. It’s often said that acting is really reacting to the people around you, so don’t be in a hurry to get your lines out and be alert to someone’s responses as they should shape yours. Social situations can be a golden opportunity to find out what someone cares about, so ask open questions and make it all about them. Then shut up and listen.

What’s your motivation, darling?

Acting isn’t an academic subject. That doesn’t mean that being well-read doesn’t matter, but leading with a purely intellectual approach and not understanding the motivations of the people around you makes for a very dull performance.

Even if the most pressing problem your donor seems to have is what colour to upholster the seats of their husband’s helicopter, ultimately they will be motivated to give by something of substance. It could be love, loss, guilt, a sense of moral responsibility or even just a fear of not belonging, but whatever it is (tax efficiency aside) it will be a feeling. In the same way that this is the actor’s starting point, it’s also the north star for your relationship with the donor.

It’s sometimes said that major donor fundraising is a dark art, but I think it’s a scientific method married to the art of being a human being. Like actors, major donor fundraisers need to be chameleons, a conduit between the very different worlds of donor, beneficiary and expert. They have to be truthful and credible, attuned to sutble nuance, able to tell compelling stories that move people to action and have the ability to bounce back from rejection. This is not a job for the faint-hearted.